|

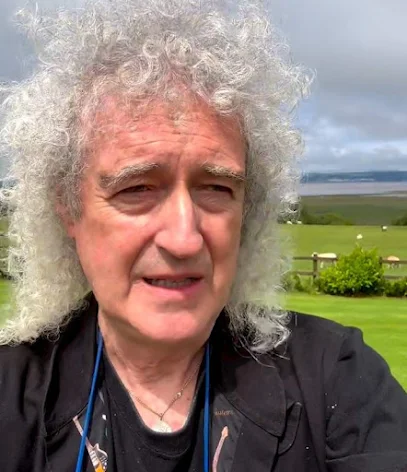

| Brian May talks about bovine TB and the badger cull. Image: Screenshot from the video below. |

Vivian, a very decent and caring farmer [who owns the farm where he made the video on this page], took meticulous care of his cattle, until one day, out of the blue, the whole herd failed the SICCT skin test for bovine TB, and he lost them all, along with his livelihood, and his family's whole way of life. He and his wife have fiercely fought back, as you'll see in the documentary we're making with the BBC. But in the ten years since this happened, the situation has only got worse for cattle farmers, indicating that a massive rethink is required, focussing on transmission of the pathogen within the herd, instead of clinging to the notion that the problem in cows can be solved by messing with surrounding wildlife, and testing and removing cows using a completely unreliable skin test.

Please view the whole video. Sir Brain needs to be listened to. He is making a documentary for the BBC on bovine TB. It should be great because he is a smart guy and a seeker of the truth unlike the British government which is populated with a bunch of idiots. Well, not quite but they are so political that the truth sometimes (often?) comes second to the politics.

How do badgers transmit bovine TB to cattle? There must be some transmission but it is clearly not as significant as the cattle themselves being a reservoir.

Badgers (Meles meles) have been identified as a wildlife reservoir for bovine tuberculosis (bTB), a disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis, which can affect cattle and other animals. The exact mechanisms of transmission of bTB between badgers and cattle are not fully understood, but there are several ways through which this transmission can occur:Direct Contact: Badgers and cattle can come into direct contact with each other, primarily in areas where they share habitats. Close contact between infected badgers and susceptible cattle can lead to the transmission of the bacterium through respiratory secretions, saliva, urine, and feces.

Environmental Contamination: Infected badgers can shed the bacteria in their urine, feces, and other bodily fluids. These contaminated materials can persist in the environment, especially in areas where badgers are active, such as their setts (burrows). Cattle grazing in these areas might come into contact with the contaminated environment and ingest or inhale the bacteria.

Shared Feeding Areas and Water Sources: Badgers and cattle might share common feeding areas or water sources, increasing the potential for indirect contact and transmission of the bacterium.

Aerosol Transmission: It is also possible that the bacteria could be aerosolized in badger setts or other areas where badgers are active, and cattle could inhale these aerosols, leading to infection.

It's important to note that the exact role of badgers in transmitting bTB to cattle is still an area of ongoing research and debate. Various factors, such as the density of badger populations, prevalence of infection, and environmental conditions, can influence the risk of transmission.

Efforts to manage bTB transmission between badgers and cattle often involve implementing strategies such as culling infected badgers, improving biosecurity on farms, and developing vaccination programs for both cattle and badgers. However, these strategies can be contentious and have sparked debates over their effectiveness, ethical considerations, and potential impacts on wildlife populations.

Environmental Contamination: Infected badgers can shed the bacteria in their urine, feces, and other bodily fluids. These contaminated materials can persist in the environment, especially in areas where badgers are active, such as their setts (burrows). Cattle grazing in these areas might come into contact with the contaminated environment and ingest or inhale the bacteria.

Shared Feeding Areas and Water Sources: Badgers and cattle might share common feeding areas or water sources, increasing the potential for indirect contact and transmission of the bacterium.

Aerosol Transmission: It is also possible that the bacteria could be aerosolized in badger setts or other areas where badgers are active, and cattle could inhale these aerosols, leading to infection.

It's important to note that the exact role of badgers in transmitting bTB to cattle is still an area of ongoing research and debate. Various factors, such as the density of badger populations, prevalence of infection, and environmental conditions, can influence the risk of transmission.

Efforts to manage bTB transmission between badgers and cattle often involve implementing strategies such as culling infected badgers, improving biosecurity on farms, and developing vaccination programs for both cattle and badgers. However, these strategies can be contentious and have sparked debates over their effectiveness, ethical considerations, and potential impacts on wildlife populations.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments are always welcome.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.